By Kevin Nance

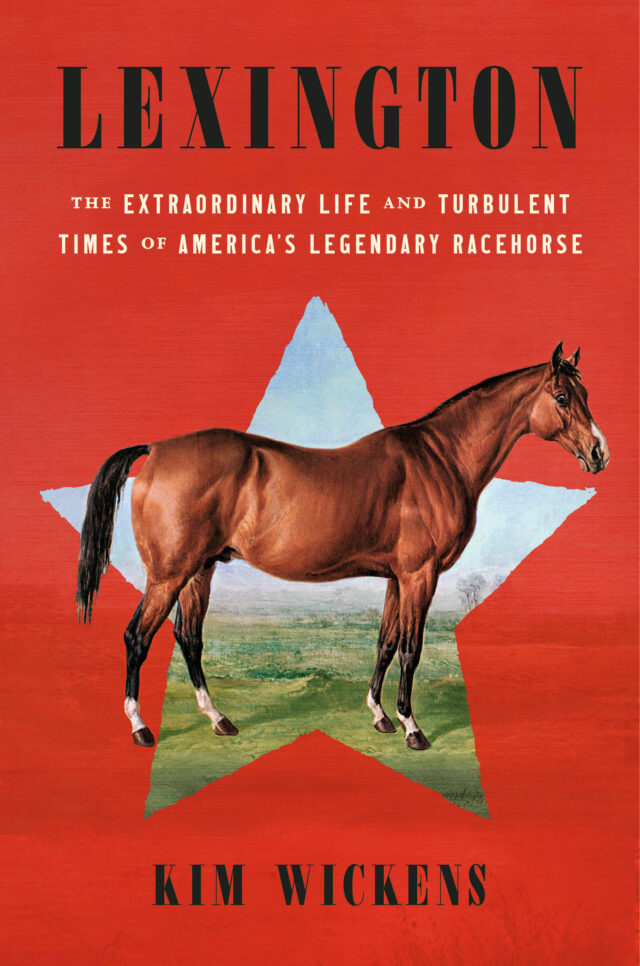

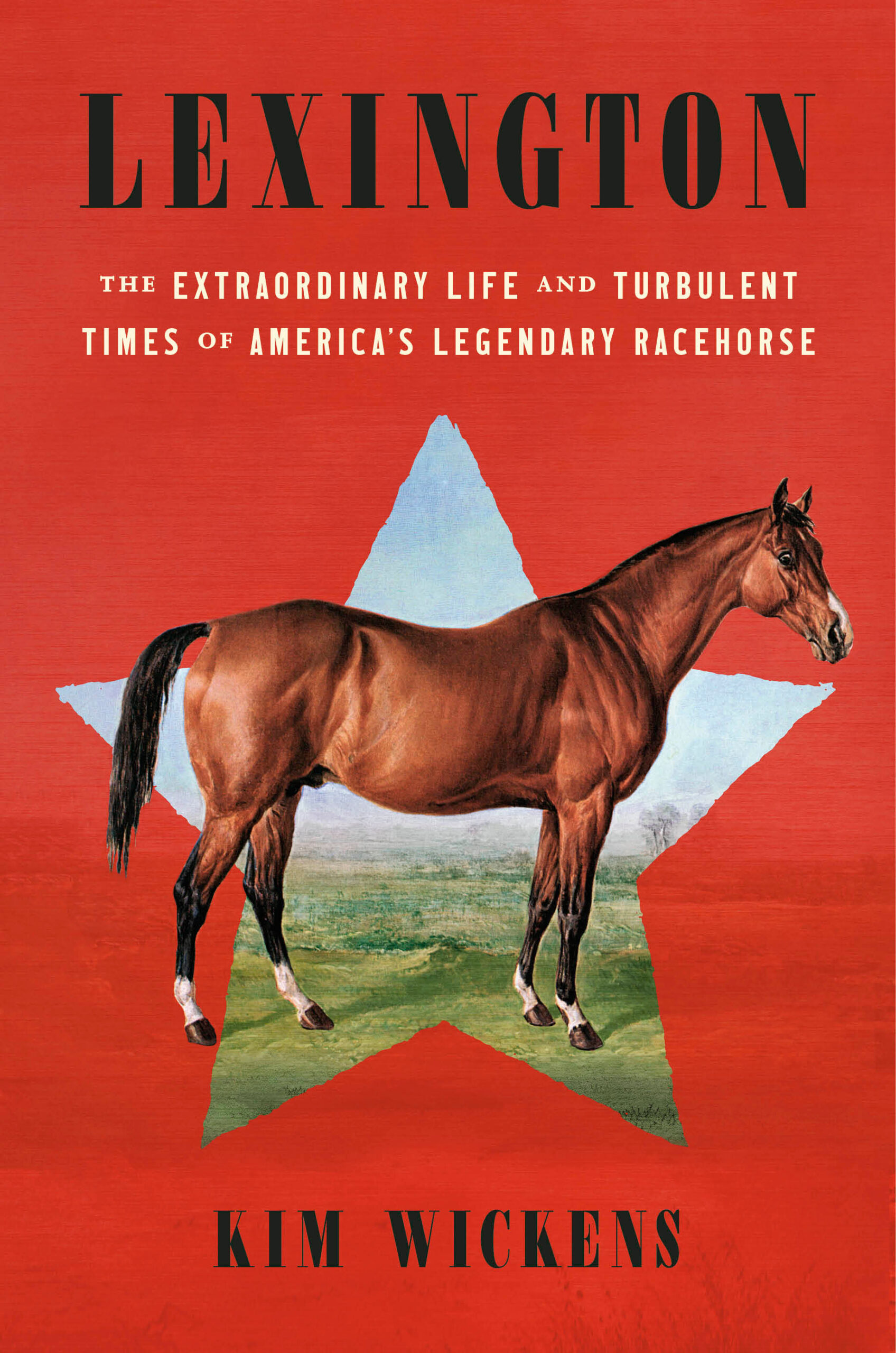

Kim Wickens had been researching and writing a nonfiction book about the great 19th century racehorse Lexington for years when she learned that the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Geraldine Brooks was at work on a novel on the same subject. Brooks’s Horse, published last year by Viking Press, was destined to become a critical darling and bestseller.

Wickens, a former criminal defense lawyer making her debut as a published author, had far lower expectations.

“I was terrified,” Wickens says in an interview at her recently completed home in the Georgetown area. “I thought it was over for me, right there and then.”

“We were nervous, thinking that this was going to be damaging for our book,” says Susanna Porter, the vice president and executive editor who acquired and edited Wickens’s sprawling manuscript. “Then we realized the two books actually complement each other so wonderfully. It’s a nice coincidence.”

In the end, the books aren’t much alike. Set in two parallel timeframes, Brooks’s novel is largely the story of two black men, including a real-life (though minimally documented) groom named Jerrit, who worked with Lexington during the thoroughbred’s long career as America’s most successful sire. (Using the creative license of fiction, Brooks brings Jerrit into Lexington’s orbit much earlier.)

Wickens, by contrast, ushers Lexington himself, named for the city of his birth, into sharp focus at center stage, albeit surrounded by a colorful cast of owners, trainers, jockeys, and breeders of the era. Spirited and a bit impulsive—he once seriously injured himself by running wild through a cornfield—Lexington was to the 19th century what Man o’ War was to the 20th: a celebrity in his own day, known for his strength, stamina and the courage and heart necessary to win in the harshest conditions.

“It was a very different time,” says Wickens, who has loved horses since her grandfather took her to her first race and later bought her first quarter horse. (Later she fell in love with dressage, and owns and trains three horses—including the tall and handsome Farraz,

In America in the 1850s, in fact, horse racing was beyond grueling, at least for the horses. Relying on exhaustive research and a keen eye for colorful detail, Wickens paints a harrowing portrait of the sport in that era. While today’s top races are a maximum of two miles long, top-level races in the antebellum period featured multiple heats of four miles, meaning that champions such as Lexington were required to run as many as 12 miles in a single day. (Between heats, teams of grooms—precursors of NASCAR pit crews a century later—would rub the horses’ aching muscles down with whiskey.)

Despite the fact that he was partially and increasingly blind, Lexington smashed the world speed record for a four-mile race in 1855, a feat celebrated all over the nation despite the storm of the Civil War gathering on the horizon. (In an earlier race, Lexington’s main competitor, a filly named Sally Waters, was so worn down that she never raced again, and may have died from the after effects, a month later.) After his failing eyesight forced him to retire from racing, he went on to his second career as a stallion at Woodburn Farm in Woodford County, where he established one of the great bloodlines in the history of racing. His progeny and their descendants went on to win 12 Triple Crown, and Lexington was named America’s a record 16 times.

During the Civil War, however, Lexington’s idyllic life at stud was repeatedly interrupted by

Thanks to their editors, who arranged a lunch meeting, Wickens and Brooks finally got together and compared notes last year. “I never encountered her while doing the research,” Wickens recalls, “but she was so generous and nice. It was great to meet her finally.” Brooks ended up providing a fine blurb for Lexington, calling it “a fascinating account from start to finish.”

Truth, it turns out, really can be stranger than fiction.

This article appears on pages 10-11 of the October 2023 issue of Ace. To have the digital edition delivered to your inbox each month, click here.